In recent years, the Israeli high-tech industry has reached exceptional achievements on a global scale, placing Israel at the forefront of global technology innovation.

But this industry is not exempt from problems and challenges, chief among them the need to assure the continuation of the human capital advantage, in light of the grave shortage in skilled personnel (engineers, programmers), the crisis in technology studies and the maturation of the high-tech industry which is causing investors to prefer entrepreneurs who have already proven themselves.

Above all, there is a need to find new growth engines.

In recent years, the Israeli high-tech industry has reached exceptional achievements on a global scale. High-tech exports, for example, were 45 billion dollars in 2017, approximately 45% of total Israeli exports, while the scope of capital raised and the scope of exits reached new heights.

Anyone who examines the Israeli economy over the past three decades understands that Israel has gone from a sleepy economy to a technology tiger by virtue of high-tech.

Israel has already surpassed the per capita GDP of superpowers like France and Britain and is approaching those of industrial giants like Germany and Japan.

These achievements constitute the expression of record continuous technological growth that has lasted more than 25 years and whose source is in the unique integration between several different factors: the maturation of products of technological education; civilian applications of defense industry and government support for raising venture capital – that has created a developed infrastructure of private venture capital; a high level of entrepreneurship and innovation; excellent human capital, based among other things on immigration from the FSU, which brought a large pool of talented engineers; and the shift in the emphasis of the global computer industry from hardware to software – which developed, beginning in the 1990s, a wide opening for the entrance of dozens of Israeli companies which presented a significant comparative advantage in the global technology market.

Indeed since the beginning of its existence (actually, since the beginning of Zionism), Israel has placed emphasis on scientific research and human development, among other reasons as a response to its inferiority in natural resources and as a response to the Arab boycott, but in the past three decades Israel has doubled its efforts.

Between 1984 and 2014, for example, Israel registered growth of 378% in the number of students in universities and colleges, growth of 223% in national expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP (from 1.3% in 1984 to approximately 4.2% in 2014) and Israel is ranked today in first place among 148 economies in innovative capacity, in second place in entrepreneurship and in third place in global innovation.

In fact, since the 1980s Israel has created one of the most vibrant technology communities outside of Silicon Valley.

The groundbreaking products in the Israeli high-tech sector extend over a wide range of fields – internet, ed-tech, cyber, fintech, gaming, mobile technologies and apps, medical devices, sophisticated defense and security products, agro-technology, cleantech, food tech and more. This is all taking place despite global investors’ declining enthusiasm for investment in technology companies, troubling security problems (three intifadas and several military operations) and a hostile atmosphere towards Israel, especially in Europe.

Israel’s strengths in the field of innovation and specifically the value of its human capital have brought a stream of technology companies here from around the world.

Currently more than 300 leading international companies, such as Facebook, Microsoft, IBM, Intel, Google, Apple, Cisco, Motorola, Philips, Applied Materials, Siemens, HP and EMC, have chosen Israel as a destination for establishing R&D centers and have acquired dozens of Israeli startup companies (see below). These companies provide direct and indirect employment to approximately 300,000 workers.

The Unique Israeli Ecosystem: Connection between Military-Industry-Academia

One of the reasons for Israel’s technological success in the global arena is the accelerated growth and development in recent years of a unique technological ecosystem.

This ecosystem rests on four pillars: military-defense development, which radiates and spills over into the civilian sector; the close links between industry and academia; the arrival of multinational companies in Israel and the integration of all these elements. The technology sector in Israel owes a great deal to the defense/security establishment. Each year the elite intelligence and computer units of the IDF, and especially Unit 8200, release thousands of alumni with exceptional talents into civilian life who integrate into the Israeli cyber industry. This industry has merited 20% of total new investments.

The Israeli situation, which is so complicated from an existential security perspective, is responsible for the continuum that exists between the educational system and the military.

The military selects the most suitable people from within the Israeli educational system at early stages, invests a fortune in training them, and immediately places them at the technological forefront. No entity knows how to quantify this investment in human capital, which afterwards serves as a reserve for high-tech (see the entry on the quantity of startups for which former 8200 members are responsible), but there is no doubt that it must be taken into account.

The spread of human capital, ideas and budgets from the military to the civilian market is one of the prominent force multipliers of the special technological ecosystem that has been created here.

Anyone who visits the new high-tech park in Beer Sheba – which can successfully compete with any advanced technology park in the world – can see for themselves how strong the foundations of the Israeli ecosystem are and how they serve as a force of attraction for multinational companies.

The connection between Deutsche Telekom, for example, and Ben Gurion University, and between the company and the military – that is relocating the teleprocessing and intelligence units here – has created an exceptional core of technology cooperation (for example, in the cyber field).

When all this happens in a relatively small market, these multipliers have excess power.

The security establishment and the intelligence establishment need experts in analyzing, understanding and basing decisions on a huge flow of constantly changing complex, multi-dimensional data.

Therefore, Israel developed capacities to deal with data in three categories that are growing globally: Business Intelligence (BI), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Big Data.

These abilities and talents have permeated from the military sector into the civilian sector. In the wake of this, new companies and entire sectors have started, such as cyber, which are receiving a huge shot of energy.

In this context, it is also worth mentioning that at the beginning of the 1990s, the state of Israel created two programs that gave a boost to the Israeli high-tech industry, which had mainly focused up to that time on defense industries. The Yozma (Initiative) Program led to the establishment of ten venture capital funds and an increase in investments from overseas.

The better-known Incubator Program led to the establishment of technology incubators that accepted 80-100 startups each year and provided entrepreneurs with financing and widespread assistance. The two programs created the venture capital industry in Israel, which later turned Israel into the “Startup Nation.”

Until the beginning of the 1990s, most of the necessary components of the ecosystem were operating in Israel, among them institutions of higher education and research centers, service providers including patent and accounting offices, global companies and more.

The venture capital industry was the missing piece of the puzzle and with its completion, the path to success in promoting entrepreneurship and innovation became faster and simpler.

In recent years, an additional component has integrated into the Israeli ecosystem in the form of accelerator programs.

These accelerators assist in increasing the rate of progress of startups in the early stages with the goal of assisting companies in getting through one of the most complex hurdles – obtaining initial funding.

The accelerators are characterized by short activity cycles and are distinguished from one another in kind and scope of the services offered, but together they are a growth engine for additional startups.

Characteristics of High-Tech Companies

In recent years, the technology industry in Israel has been the growth engine of the Israeli economy.

It has the greatest contribution to exports from the state of Israel (approximately 50% of all exports, with a leap of 3,700% since 1984), it has the highest level of access to capital markets in the world and it is in fact the only sector of the economy that has succeeded in raising foreign equity capital at the highest rates, in contrast to the government, the banks and the electric company that have raised debt financing only.

The success of the Israeli high-tech industry, that reached its height in 2015, attracted, on the one hand, more money into the Israeli market, with global and local investors who seek part of the enticing yields of investment in high-tech, especially in light of low worldwide interest rates.

On the other hand, more and more entrepreneurs are establishing new enterprises, like mushrooms springing up after rain.

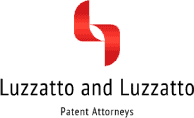

Currently 6,650 high-tech companies are operating in Israel (as of 2017), among them 4,750 are startup companies at various stages of development. Approximately 77% of all the companies have raised capital at least once from an external source such as government funding, angels and venture capital funds.

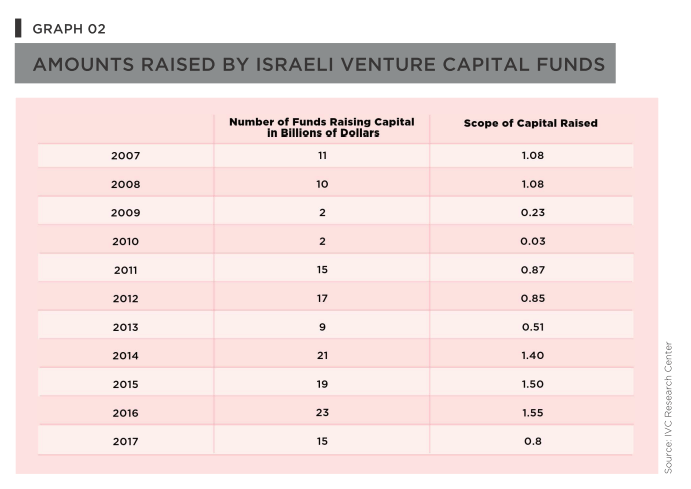

The division of high-tech companies into sub-categories reveals that approximately 25% are in the field of internet, 20% in communications, 19% in the IT and enterprise software field, 17% in life sciences, 9% in cleantech, 2% in semiconductors and 2% in other fields.

The scope of direct employees in the high-tech field is estimated at approximately 300,000 people, but it is worth remembering that the scope of indirect employees is higher. In fact, for every position in high-tech, there are four additional positions in service fields.

Israel also has one of the most developed infrastructures in the world in all parameters required for a flourishing technology industry.

The quantity of engineers and scientists in the population is among the highest in the world, as is the number of new enterprises relative to the population, which is the highest in the world.

We also note that in Israel approximately 90% of the inventors are local, similar to India, China, Japan and Korea, such that most technological innovation in Israel originates with Israeli inventors.

Israel Puts Itself on the World Car Map

2017 will enter the history of Israeli high-tech as the year that Israel became a significant player in the car industry alongside places like Germany and Detroit.

The change trend began a few years ago, with the opening of the American GM development center and visits from a delegation of representatives the leading global car manufacturers, who streamed into Israel unceasingly.

Among the prominent events of 2017 were the acquisition of Argus Automotive Cyber Security by the German Continental firm for approximately 450 million dollars.

The acquisition of Mobileye by Intel for 15 billion dollars is also part of this trend and is likely to turn Jerusalem-based Mobileye into a core technology in all autonomous cars. In addition to these events, there was a series of significant investments in companies developing technology in the field. The growth of the auto technology industry in Israel is based on utilization of the comparative advantages of Israeli high-tech, among them technology in the field of machine vision, which comes from the defense industry.

It may be assumed that Israel is at the height of a wave that will continue in upcoming years and influence local industry.

Industry Maturation

According to the Dun and Bradstreet research company, there is a clear trend of annual growth in the number of large companies – those employing over 100 = that increased in the past year.

Currently, 385 large firms operate in Israel – approximately 6% more than their numbers in 2015.

Since 2010 their number has grown by 4% annually.

Moreover, today there is more money in the market, but it is invested in fewer companies, as noted by the IVC research data.

The difficulty in raising funds is felt mainly in the initial stages; the sums raised by those who do succeed are larger than in the past and are set according to unprecedented valuations; the intervals between rounds of capital raising are decreasing; exits are fewer and Israeli companies are growing; and most of the money is found in companies at advanced stages.

The result is that in order to succeed in raising large sums of money in the early stages, companies need to respond to more rigid criteria than in the past. With the maturation of the high-tech industry, conservatism is rising.

In other words, rather than enterprise establishment and investment broadening to larger segments in Israeli society, the number of enterprises that succeed in raising investment in the early stages is actually shrinking.

The data from IVC reveal that this is a gradual change: in 2014 estimated valuations in early stages began to rise, and with them the sums raised. The number of deals declined from 708 in 2015 to 659 in 2016, with a continued increase in the total sums raised – which indicates growth in the scope of the deals.

Also in 2016, the increase in sums raised in early rounds became more moderate, and the numbers of round B decreased by 30% relative to 2015.

The lack of ability of companies who relatively easily raised funds in seed and A rounds in 2015, to raise funds in further rounds in 2016 was expressed in a decrease in the number of deals in early rounds in 2017: 140 funding deals for companies at the seed stage, in contrast to 196 in 2015.

Recently, large strategic investors have also entered Israel.

In 2017, the Japanese SoftBank raised a fund of 100 billion dollars and began investing large sums in companies around the world and also in Israel: SoftBank led with an investment of 120 million dollars in Lemonade and also invested 100 million dollars in the Israeli Cybereason company.

This pushed many funds that had focused on more advanced stages to also get into seed investments.

Exits and Raising Capital (1): Intellectual Property as a Comparative Advantage

In-depth reflection on the Israeli high-tech industry makes it possible to better understand the intellectual property situation in Israel because of the clear linkage and inseparable connection between the technology industry and intellectual property. In large measure, intellectual property – in its broadest meaning – reflects the essence of technological development, and frequently even predicts it, and this is because of the simple fact that entrepreneurs and developers register patents on their developments before they enter the market.

The matter is illustrated even more in Israeli startups that have been sold to giant overseas corporations.

The scope of acquisitions by giant global firms in recent years exceeds everything known from other economies. Thus, for example, Intel acquired 14 companies in a scope of 17.4 billion dollars, Cisco acquired no fewer than 13 Israeli companies in recent years, with a total worth of 7.1 billion dollars, HP acquired 6 companies in a total scope of 5.5 billion dollars, Marvel acquired 4 companies in a scope of 3.5 billion dollars, IBM acquired 14 companies in a scope of 1.6 billion dollars, Covidien acquired for companies in a scope of 1.6 billion dollars, Microsoft acquired no fewer than 22 Israeli startup companies in a total scope of 1.5 billion dollars, Broadcom acquired 12 companies in a scope of 1.2 billion dollars while Google acquired 10 companies in a scope of 1.2 billion dollars.

Let us emphasize that these giant corporations acquired Israeli startups for the value of the innovative technologies they had developed that constitute intangible intellectual assets, that is, intellectual property.

These acquisitions did not include cash flow, accumulated customers, or scope of sales that justified the high values that were paid for these companies.

It was primarily the technological innovation, which is, as stated, of great worth, that justified this. There is also no doubt that intellectual property will continue to be the focus of the attractiveness of Israeli companies for multi-national corporations.

In other words: intellectual property reflects technological innovation, just as this is expressed in intangible intellectual assets, and constitutes the core of value in processes of sales and acquisition of technology companies.

This can also be seen through the prism of venture capital.

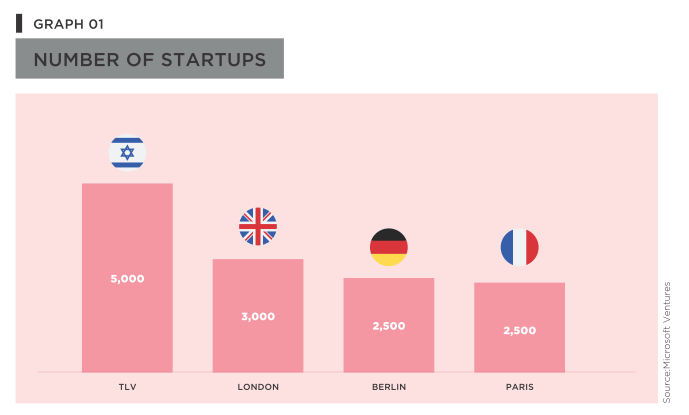

From 2007-2017, venture capital investment in Israel was 21.8 billion dollars, with consistent and persistent growth over the years.

Israeli technology companies raised a record amount of capital investment in 2017, a total of 5.24 billion dollars – a record since 2013 – and this was in 620 deals.

This is an increase of 9% over 2016, in which 4.83 billion dollars was raised in 673 deals. However, it is worth paying attention to the fact that over the years, the portion of Israeli funds in the total investments has been decreasing, which increases the dependence on foreign investment, mainly from the United States.

Another dimension of the growth of the high-tech sector is expressed in the scope of new startup companies that open each year.

These companies are significant producers of technological innovation and intellectual property even if they do not succeed in engineering an exit.

And indeed, from the IVC data, it appears that in the years 2013-2017, 4,826 startups were established in Israel (the 2017 data relates only to the first half of the year). This is an exceptional level and it well demonstrates the power of local innovation.

It is true that quite a number of startups close and some of them do not succeed on returning investment, but the scope of innovation that they create – which is also expressed in the scope of intellectual property – is completely out of proportion to the scope of the population.

We can see that in 2017 423 startup companies were opened, a decrease from 2016 in which 951 new companies were established, but in 2017 fewer companies closed: 181 versus 441 in 2016.

The field of venture capital in Israel behaves like an upside-down pyramid.

At the tip of the vertex are the angel investors at the pre-seed stages and at the wide base of the pyramid are the foreign funds, which usually invest in the second and third rounds in companies that are already showing growth.

In the middle are entities like incubators, crowdfunding and micro funds that invest in seed stages and Israeli funds and foreign funds in partnership with Israeli funds that invest in the first round of funding.

Old slide from the previous report – Israel VC Sector – Investors’ Ecosystem

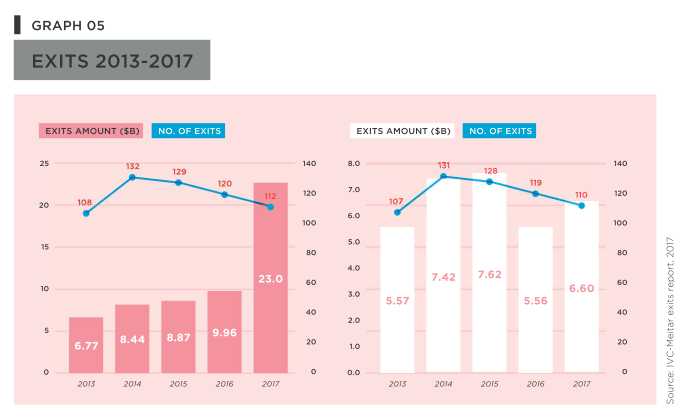

Regarding exits, in 2017 the amount of exits doubled and nearly tripled compared to 2016 and reached 22.6 billion (an all-time record amount, including the huge deal for the sale of Mobileye to Intel).

The average return on investment in the case of exits by year stands at 4.2 for the first half of 2017, compared to 9.3 for all of 2016, 4.2 for all of 2015, 5.4 for 2014, and 4.3 for 2013.

The High-Tech Sector: Impressive Achievements and Structural Challenges

As stated, the Israeli technology industry has attained exceptional achievements over the past three decades.

A long term analysis of trends shows that an unprecedented number of start-ups are operating in Israel, alongside development centers of multinational companies, which alongside excellent academic institutions and a security establishment with a clear technological orientation have created an ecosystem that is unique in the world.

According to data from the IMD Research Institute – which studies market conditions of countries around the world – Israel leads in all essential and important parameters for building and establishing a technology industry that develops innovation: technological and scientific infrastructure; a sophisticated capital market; flexibility; approach to globalization; developed venture capital; a skilled work force; a courageous business sector; and broad scientific research.

According to the same study, Israel is ranked in first place in innovative capacity, in second place in entrepreneurship, and in third place in global innovation. Above all, the state of Israel is blessed with entrepreneurial spirit, human capital and exceptional innovative talent. No one can take from us the advantages of the Israeli engineer: complex, systematic vision; effective teamwork without class importance; and ambition to achieve the impossible.

Despite all this, we cannot ignore the fact that the challenges of the high-tech industry are growing rapidly and require wiser, more effective intervention by the government in order to preserve Israel’s comparative advantage. These challenges include:

- A hyper-competitive global environment

- A sophisticated industry that is changing at the fastest pace

- The diversity of technological fields, in which each field has unique characteristics and needs

- Complete dependence on external and diverse target markets and the need for increased international activity

- Funding sources that are mainly foreign and are exposed to the volatility of world markets

- Lack of mature companies that can be an employment anchor in Israel

- A serious shortage of engineers and professional personnel for the high-tech industry

- Difficulties in technology education to create a reserve of labor for a knowledge-intensive industry

- The concentration of Israeli high-tech in a narrow geographic sector between Herzliya and Tel Aviv and minor presence in the rest of the country and especially in the periphery.

In addition to maintaining a strong and leading high-tech industry, the government must work to advance technological innovation in other industries and sectors in order to increase the competitiveness of the Israeli economy.

Recently, a number of figures have popped up in the media that have raised a red flag regarding the future of Israeli high-tech.

The chief economist of the treasury, Yoel Naveh, published a survey according to which the status of Israel as a leader in global technological innovation has been damaged.

The survey determined that high-tech no longer serves as a growth engine of the economy as it has in recent years. The Prime Minister, it was reported, is considering importing software engineers into Israel due to the shortage of high-tech workers. The Finance Minister stated at a press conference that he is considering giving relief to high-tech companies that are requesting mergers in order to solve the problem of the shortage in skilled personnel. At the same time, the Minister of Taxes sought to examine the possibility of relaxing the requirements of the law for encouraging investment in order to enable more high-tech companies to benefit from it. Finally, a new report from the Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy revealed that for the first time, South Korea surpassed Israel in national spending on research and development as a percentage of GDP, and this was prior to the new report published by the OECD.

Despite this, analysis of long-term trends shows that there are an unprecedented number of startup companies operating in Israel, alongside development centers of multi-national companies.

The amount of foreign investment and the number of new startup companies show a fixed increase every year.

The exits are a source of income that returns to the country, while entrepreneurs who made successful exits serve as private investors and consult with startup companies, thus encouraging innovation. Israeli companies are maturing and are creating more value and business activity and therefore need funding rounds that reflect high valuations.

The Crisis in Technology Education

In the opinion of this report’s authors, one of the central challenges to Israeli high-tech is inherent in the current crisis in technology education.

There are disturbing signs of a budding crisis already happening, among them the consistent decline in the number of students completing five matriculation units in mathematics (prior to the launch of the new Education Ministry program), for these are the main potential target population for academic studies in science and engineering fields and the criterion for measuring high schools according to the percentage of success in matriculation and not according to the quality of the matriculation certificate and its ability to assure acceptance for academic studies – a fact that does not encourage students to choose advanced science studies.

This is in spite of the fact that success in a high number of learning units in mathematics and science is a good predictor of academic success in higher education in engineering or sciences.

The full meaning of the weakening of school science studies is already being felt.

In Israel today there is a shortage of 10,000 engineers. The significance is that if in the past Israel relied on its human capital, in a number of years Israel will confront a significant problem, which will cause companies to move their activities to competing countries. This is one crisis that the state of Israel cannot afford.

The solution to the problem is not simple, mainly because it is not in the hands of one entity.

There is no magic solution – what is required here is mobilization of holistic, long-term processes with involvement from the government, the private sector and the third sector.

The program to strengthen mathematics studies is a step in the right direction, especially in the adoption of the roundtable model that puts private entrepreneurs, relevant government ministries, academics and education NGOs side by side.

However, mathematics is not enough, and it is impossible to be satisfied with only high school and matriculation studies. We must think about the entirety of science and technology learning, and initiate a program for the educational continuum beginning with elementary school and continuing through middle and high school, military service and academic studies, one that does not stop even after placement in technology companies.

If we return to the data, we discover that in 2014 only approximately half of the graduating cohort completed full matriculation eligibility.

Out of those eligible for a matriculation certificate in this cohort, the percentage who took advanced mathematics exams was on a downward trend.

Among those eligible for matriculation, those who took advanced mathematics exams and advanced science and technology (STEM) exams in addition (in physics, chemistry, biology, computer science and electronics) was on a downward trend. Those high school students who are eligible for matriculation certificates at an advanced level of mathematics and especially those who take the test for five matriculation units in mathematics and in an additional advanced STEM subject, these are the potential future college students in science and technology subjects. In addition, there was also a decline in numbers of bachelor’s degree graduates in most science and technology subjects.

Therefore, the central solution is to be found in increasing the percentage of high level matriculation graduates in mathematics and sciences, through a conceptual, multi-level STEM education continuum, beginning with pre-school through the end of high school, professional school, and technology training tracks in the military. To this must be added an important stage of providing bonuses and incentives for academic study in the sciences.

This can be done through granting scholarships to students who complete advanced matriculation in mathematics, English and sciences, or providing a free year of study at colleges and universities in science and engineering subjects, or through individual grants.

Increasing the Number of Workers in Knowledge-Intensive Sectors

The government recently made a decision to allocate the sum of 900 million shekels to increase the number of workers in knowledge-intensive sectors.

In this context, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu emphasized correctly that the program is intended to preserve Israel’s comparative technological advantage through “incentives to the high-tech sector and increasing the number of engineers and scientists and significantly increasing the number of graduates of relevant departments in universities.” Netanyahu also mentioned that “the central problem that we have in the high-tech sector is responding to the demand, and for this purpose we need personnel selection at the highest level.”

However, this program is not enough.

In order to meet this acute challenge the government must have a broader, long-term vision, while dealing with the fundamental factors that have brought us to the current situation, chief among them, as stated, the weakness in STEM education. There is no place for patchwork tactics. Rather, what is required is a comprehensive, coherent long-term strategy.

Alongside this there is a need for a comprehensive change in the public consciousness regarding professional education.

Currently professional technological education is considered inferior.

One of the reasons for this is the sense that it establishes ethnic discrimination by “tracking”, that is, steering children from the geographic and urban periphery into vocational tracks in contrast to steering children from the center into theoretical tracks. However, the content world of STEM professions has innovated and advanced so as to be unrecognizable: students in technological and vocational education can today study a variety of exciting and advanced subjects beginning with robotics, software and electricity and ending with automobiles, construction and architecture. All these require technological-scientific teaching personnel, of which there is also a shortage.

Therefore, a courageous government program is also needed to address this aspect, while providing incentives for integration of teaching by graduates of science and engineering programs (such as high-tech workers and retirees) after they receive professional development training in teaching, doubling the salary for all excellent teachers in mathematics, sciences and technology through personal contracts and administrative flexibility for school principals in choosing teachers to teach sciences.

An additional strategic solution can be found in the integration of populations that currently do not participate in the high-tech branches – residents of the periphery, ultra-Orthodox, minorities, and a portion of the population of women.

All these are not sufficiently involved in sciences, engineering and R&D. This situation creates a rare opportunity for changing the labor market in Israel and reducing social gaps.

The shortage of technological personnel is an acute and ominous challenge, but one that is solvable.

Just as we have known how to get out of distress and cope with challenges in the past, so in this situation we must pull ourselves together and face this challenge, which threatens the definition of Israel as the “Start-Up Nation”, while taking advantage of the challenge as leverage for achieving national socio-economic objectives.

Additional Improvement in the Business Climate

An additional aspect that should raise a red flag is connected with the fact that Israel is currently operating in an extremely competitive environment – China and India are breathing down our necks and every self-respecting country in the world is investing significant sums in R&D.

In parallel, the Trump administration announced a massive reduction in the level of taxes on corporations, something that is liable to attract many Israeli high-tech companies, whose efforts are already directed to that market, to the United States.

The government must continue to foster a sympathetic environment for innovation and entrepreneurship.

In this context, it is also important to remove bureaucratic and regulatory barriers, to create laws that encourage investment from at home and abroad, and to implement long-term programs that will decrease uncertainty and attract international bodies to open and increase activities in Israel.

A significant part of meeting these challenges depends on the new Innovation Authority that will replace the Chief Scientist’s office.

The Authority has the ability to quickly mobilize solutions and tools for supporting the competitive capacity of Israeli high-tech with as few bureaucratic restrictions as possible.

In parallel, we must work to establish a more favorable tax environment and to restore incentive programs that were used in the past to encourage institutional investors to invest in this important and profitable channel.

We must remember that venture capital funds are the main funders of young technology companies and over the past 20 years have been the main growth engine of the Israeli technology industry.

In this context, the topic of investment in R&D is critical and particularly conspicuous (in a negative sense) is the government’s contribution, which has been in a continual decline over the years and now stands at 20%.

This is offset, luckily, by an increase in investment from the business sector and multinational companies, but currently, less than 5% of government investment in R&D is invested in the business sector, which puts Israel in a comparatively low position relative to western countries.

Growth in Mature Companies

Over the past half-century, hundreds and thousands of high-tech companies have been established in Israel, but only about 50 have broken through the limits of imagination and attained market valuations over a billion dollars.

Among them at least 14 companies reached this valuation in the past two years.

Without entering into the discussion that has been going on in recent years about whether one should encourage the sale of startup companies at the technology stage, or try to grow them into significant leading companies in their field, in the opinion of this report’s authors, both alternatives are necessary for the continued growth of the industry, in which companies that are acquired in relatively early stages continue to constitute a source of attraction for acquisition by international companies. But the big challenge to the industry in the next 25 years is to develop 50 local companies with sales of approximately one billion dollars a year.

Currently the number of companies fitting this criterion is not more than ten.

Encouraging Institutional Investment in High-Tech

An additional concerning aspect is the topic of financing. More than 90% of the venture capital investment in Israel comes from foreign investors.

We are witnessing a situation where the primary beneficiaries of the Israeli high-tech and life sciences industries are American pension funds and not the Israeli public.

We definitely see a place for increased participation of institutional investors in direct investment and through Israeli funds, as happens in the United States and other developed countries.

This is an anomalous situation: on the one hand, institutional entities are sitting on mountains of shekels in a desperate search for yield-bearing investment channels, and on the other hand, they avoid investing in the flagship of the Israeli economy, in their own harbor, which is a destination for investments from foreign institutional entities (that is, 90% of the investors in in venture capital funds are foreign).

That is to say, what is good for foreign nations is not good for us Israelis.

Moreover, in contrast to the situation in the United States, in which most of the money invested in high-tech comes from pension funds, insurance companies and other institutional investors, Israeli pension funds have hardly been involved in the successes of companies such as Chromatis, Mellanox, Waze, NDS and others that registered phenomenal yields from initial investments through sale or stock issue. Indeed an anomaly.

It is important in parallel to re-educate the market and those who are saving.

The market tends to measure the success of institutional entities in the short term, while pension and provident funds serve as long term investments. As a result of that, the yields on these funds need to be measured over time and create profits in the long term, similar to the yield profile of the high-tech companies.

In fact, this is the advantage of institutional entities over regular venture capital investors – their long-term outlook. This also has importance from a national perspective – they can aid the growth of high-tech companies over time, in contrast to investors who are interested in actualizing their investment through the sale of the company and getting out, with whom it is hard to build a company for the long term.

However over and above the change in institutional behavior, the government has an important role to play in changing the rules of the game in the capital market. In the past, the Treasury adopted an initiative to launch the “Comparative Advantage” program which was meant to provide a safety net for institutional investment in high-tech.

This was an excellent program but limited in time and budget that ended with a weak response. A safety net for institutions should be restored, at least on a portion of their investment, as was the policy of the Treasury a few years ago.

In fact, the country has the obligation to work with determination and perseverance and to enact a number of policy measures in order to encourage institutional investors to invest in Israeli high-tech.

Shifting of only 1% of the funds of institutional entities, valued at approximately 1,200 billion shekels, into investment in Israel high-tech, would enable the technology sector to take off again. It is clear that this investment is not without risk, but it is certainly more intelligent than investment in Eastern European real estate.

By the year 2020, the sum of managed pension assets is expected to double and reach approximately 2.2 trillion shekels.

It is a matter of national economic importance of the first order that at least a small portion of these giant sums be directed to investment in Israeli high-tech.

Wanted: A New National Alignment

The importance of Israeli high-tech to the national economy cannot be overstated.

This sector is not measured solely by the scope of its direct or indirect employees, but also and mainly by its contribution to export, to foreign currency income, to Israel’s leadership in global markets, to the flow of investors and investment into the country, and to the foundation of Israel’s status and positioning as a technology superpower (the “Start-Up Nation”).

The data coming from the field are mixed – on the one hand, Israel continues to present strong numbers, for example in everything connected with exits and raising capital, but on the other hand, there is a certain weakness in the high-tech sector, which is seeking new growth engines.

Responsible government policies need to provide a solution for this challenge.

From a national perspective, this is currently the role of the government – to support, to push and to invest in the same successful industry which is currently at the beginning of a crisis.

If So, What is Required of the Government?

In order for the high-tech industry to continue to lead the Israeli economy, to ensure Israel’s comparative advantage in the global markets and to fully utilize its intellectual assets whose source is its human capital – which is crucial in the era of the information economy – the government must outline a comprehensive national program to develop the technology sector, based on some central anchors:

- Cultivating human capital throughout the production chain – the secondary and higher education systems, the connection between higher education and industry and the connection of these to the military technology development establishment.

- Establishing the regulatory and tax basis for additional platforms for raising capital for entrepreneurs to take the place of crowdfunding on the internet and other platforms.

- Providing an additional safety net through tax relief and benefits to investors, while directing institutional investment into high-tech.

- Providing incentives to multinational companies to establish additional R&D centers in Israel.

- Continued diversification of export efforts beyond the American market to new markets.

- Assistance to entrepreneurs, startup companies and research institutes.

- Encouragement for developing generic technology and transferring knowledge from academia to industry.

- Increasing government allocations for research and development.

- Encouragement for traditional industry to adopt new technologies that will provide added value in international markets.

As stated, everything is not rosy in the Start-Up Nation. The Global Competitiveness Report indicates that the factors that are placing the growth of the economy at risk are government bureaucracy and high taxes. This is especially true in the high-tech sector, which is very sensitive to the work environment and to the local taxation level. Companies can very easily relocate themselves and their intellectual property to a more attractive location.

Again we repeat that in light of Trump’s significant tax reforms in the United States, it will be necessary for the government to reexamine the tax regime in Israel and improve the business environment in order to ensure the continued attractiveness of Israel for foreign companies.

The challenge before us now is to ensure Israel’s technological superiority in the global arena for the future. This requires the creation of an enabling, encouraging and supportive economic environment for technology entrepreneurship along the entire production chain. This requires increasing allocations for research and development, both on the part of the government and the private sector. This requires cultivating human capital beginning at the elementary school level and preserving it over time. This requires a system of incentives, taxes and benefits for high-tech projects. This requires continued subsidies for basic research within academic institutions. This requires cultivating the special ecosystem that has grown here integrating the military, industry, academia and research. The goal is to ensure that constant movement between the military-defense establishment and the business-civilian sector, which in the context of the relatively small market has created huge advantages for Israel.

In conclusion, it seems that the situation that has led to the growth and prosperity of the Israeli high-tech industry is changing and in order not to wind up in dangerous ossification, new blood must be pumped into the system. As stated, some of the foundations on which the technology sector is based are still solid – excellent entrepreneurial ability, excellent academic institutions, relatively high national investment in R&D, highly developed sense of invention and ability to adapt to changing conditions in a dynamic global market saturated with competition. However some of the conditions that facilitated the prosperity of the industry are disappearing, especially against the backdrop of accelerated competition from Asian countries, and a dangerous void is beginning to emerge. This is the crucial moment for the country – it must preserve the exceptional achievements of the Israeli technology industry and lead it to the next level.

Israel therefore requires a long-term technology vision, with the government playing a central role. This vision must make Israel’s scientific-technological development a top priority and needs to be based on strong budget foundations and a lenient regulatory regime, with high level inter-agency coordination.

A market as important as high-tech, that is responsible in no small measure for Israel’s economic success in recent decades and constitutes a clear advantage for Israel in global markets, is worthy of serious treatment by policy makers. It is to be hoped that the Prime Minister, and the Minister of Finance, will be able to provide renewed momentum to the high-tech sector in Israel.

The World’s Problem – Israel’s Opportunity

Economic damage from cyber-attacks around the world is estimated in billions of dollars a year and provides a business opportunity for Israeli companies with expertise in the cyber field who are developing defensive programs at the defense and civilian level

According to experts in cyberterrorism, the expected dangers of cyberattacks include the collapse of critical or strategic national or military infrastructure, such as electricity, energy, defense systems, transportation, warning and emergency alarm systems. According to different published reports, more than 500 million cyberattacks take place on a daily basis around the world, many of them directed at giant companies.

60% of Fortune 500 companies deal with information leaks, internet fraud, and theft of data and customer information.

Each day we witness attacks on countries, militaries, banks and financial institutions, which expose the weaknesses of security solutions.

The economic damage from cyberattacks is difficult to estimate, but all the experts agree that it is in the range of billions of dollars annually. In the United States, it is estimated that the damage from cyberattacks is 100 times greater than that from physical theft, and in Britain cyberattacks have cost the British economy 48 billion dollars. Regarding Israel, according to the BBC every minute there are 1,000 attempts to attack Israeli targets. For Israel, the cyber threat is not theoretical, but a daily reality.

The state of Israel benefits from groundbreaking capability in the field of cyber defense and the world’s problem is an opportunity for Israel.

In recent years, approximately 200 companies have been operating in Israel in the cyber field and developing defense programs at military and civilian levels.

Many of the tools are already available to us and the state of Israel is perceived as a pioneer in development and application of defense programs against cyberattacks. Collaboration and cooperation between the military, the public sector, the private sector and academia are making us a world laboratory in the field and turning the worldwide threat of cyberattacks into a new economic and social opportunity.

The Vision – Turning Beer Sheba into a National Cyber Center

In the midst of this, Beer Sheba, which has been declared the national cyber capital, is becoming a giant incubator for cyber warfare companies, bringing together leading companies, international interest, workplaces for students and engineers and opportunities for regional growth.

A university that has grown in the past decade from 5,000 to 20,000 students and is a leader in the field of computer science, the establishment of the IDF technological computing campus, a high-tech park and a technology incubator for cyber security, and the fact that the national cyber headquarters is located in the new high-tech park in the city – all these are helping to turn the capital of the Negev into the world “Cyber Valley” which is exporting programs for defense on the virtual battlefield and is assisting many countries to cope with the new terror strongholds.

This is all happening in the new city high-tech park that is spread out over 350 dunams, and will integrate, alongside international and Israeli high-tech companies, the IDF technological computing units.

This move will in fact turn Beer Sheba’s high-tech park into one of the centers of the country in the coming years.

In the dedication ceremony for the park, the Prime Minister said that, “I have a vision of seeing Beer Sheba as a world high-tech center.

Ben Gurion’s vision has not yet been fully realized because there was not a business center here, there wasn’t an engine that would move the parts. In future, elite units of the IDF will be located here and even though we are talking about great technological strength, the cherry on the top will be the national cyber headquarters that will build its new home here in the high-tech park. Beer Sheba will become the cyber center of the state of Israel and one of the leading cities in the world in the high-tech field.”

Alongside strengthening Israel’s status as a technology superpower, the city of Beer Sheba and its surroundings will be strengthened.

It is estimated that in the coming years between 5,000 and 10,000 new jobs will be added around the high-tech park, with significant growth in small and medium-sized businesses in the city, the establishment of new centers for leisure and culture and relocation of tens of thousands of citizens to the south of the country.

High-tech is an important growth engine that must be brought to many regions of the country and to different populations.

Leadership in the cyber field is one of the strategic assets of the state of Israel, and it can be leveraged not only on the security plane, but also on the economic and social planes.

Relevant Articles

Regarding Patent Term Extensions in Israel